Interprofessional Collaborative Practice Between Behavior Analysts and Speech-Language Pathologists

Click here for a PDF of this document.

Introduction

The Practice Board of the Association for Behavior Analysis International is excited to share this Interprofessional Collaborative Practice Between Behavior Analysts and Speech-Language Pathologists resource document with you. The purpose of this resource document is to provide guidance to professional behavior analysts about how to work collaboratively with their speech-language pathology colleagues. The document outlines considerations regarding scope of practice and scope of competence to inform your interprofessional interactions and the interdisciplinary team decisions in which you participate.

Behavior analysts should practice in a manner that aligns with the interprofessional collaboration competencies so that their expertise in the science of human behavior can be combined with the unique expertise of speech-language pathologists to produce socially meaningful improvements in clients’ lives.

We express appreciation to the workgroup, led by Dr. Trina Spencer, for donating their time and ensuring the document accurately reflects statements about behavior analysis and speech-language pathology. We are also grateful for the support of American Speech-Language Hearing Association (ASHA), who has provided outstanding leadership to all health professions regarding Interprofessional Practice and Interprofessional Education.

Workgroup Members

Trina D. Spencer, PhD, BCBA-D

Lina Slim, PhD, BCBA-D, CCC-SLP

Teresa Cardon, PhD, BCBA-D, CCC-SLP

Lindee Morgan, PhD, CCC-SLP

Behavior Analysis and Speech-Language Pathology

Although considered a young applied science, behavior analysis has matured over the past six decades. Its premise that behavior is a product of its environment and circumstances holds that only behavior in relation to its antecedents and consequences is worthy of analysis and susceptible to modification. Extrapolated from a natural science endeavor, a set of conceptually systematic learning principles made it possible for behavior analysts to develop numerous tactics and procedures that are supported by a robust empirical literature and disseminated through rigorous university and experiential training, bringing about a new profession capable of treating a variety of human conditions.

As the profession of behavior analysis continues to evolve, there is no doubt that behavior analysts and their allied health colleagues will experience growing pains. Tensions naturally emerge when professionals advocate for their right to practice and compete for finite resources. The burgeoning population of professional behavior analysts may encounter resistance, discord, or confusion about how they fit within a human service arena alongside other health professionals. While the potential for conflict exists between professional fields such as psychology and occupational therapy, increasing tensions between speech-language pathologists and behavior analysts signal the need to provide a set of guidelines to enhance behavior analysts’ ability to engage in interprofessional collaborative practice and properly navigate their scopes of competence. Thus, the purpose of this resource document is to characterize professional behavior analysts’ responsibility for interprofessional collaboration while engaged in the treatment of a variety of conditions (e.g., autism), where there is considerable overlap between speech-language pathologists’ and behavior analysts’ scopes of practice.

Despite many differences, it may be surprising to some that the professional landscape of behavior analysis has many points of convergence with speech-language pathology. For example, many early speech-language pathologists were trained in behavior analysis and much of their treatment procedures were derived from the science of behavior and learning. As the profession progressed, however, speech-language pathology was influenced by an eclectic set of theories and not a single theoretical orientation as is the case with behavior analysis. Regardless of the philosophical origins of speech-language pathology treatments, the principles of behavior that are responsible for a treatment’s effectiveness are recognizable.

Behavior analysts’ practice is informed by a set of universal principles that govern learning and behavior change. However, knowledge of universally applicable principles does not translate to an unconstrained scope of practice or an unlimited scope of competence. Evidence of this critical misunderstanding is when behavior analysts suggest that a speech-language pathologist is not needed in the treatment of communication disabilities or when behavior analysts treat a clinical problem (e.g., swallowing) of which they have little to no understanding. Although the science of behavior is germane to all behaviors, behavior analysts should not interpret it to mean that other professionals are not needed. Nor should the elimination or replacement of other professions be the goal of professional behavior analysis.

Knowledge of universally applicable principles does not translate to an unconstrained scope of practice or an unlimited scope of competence.

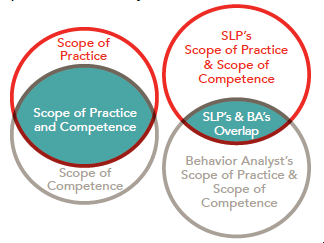

The regulation of professional behavior analysts through licensure legitimizes the practice and sets forth the profession’s scope of practice. However, a scope of practice is only the set of activities that a licensed/certified behavior analyst is authorized to engage in. That authorization is conditioned upon the professional also being competent. A scope of competence refers to the extent to which a professional can engage in specific clinical activities at a level of performance consistent with a specified standard of excellence. The difference between scope of practice and scope of competence is critically important because an individual behavior analyst is only free to practice in the space where their scope of practice and scope of competence overlap. Just because one is authorized to practice relative to a specific procedure, population, and setting does not mean they are competent to do so. The reverse is also true. Just because one is competent to practice relative to a specific procedure, population, and setting does not mean they are authorized to do so. It is up to the individual professional to seek training, consultation, and supervision when practicing outside of one’s scope of competence, and it is incumbent upon the professional behavior analyst to never practice outside of their scope of practice.

Even when behavior analysts are careful to practice within their overlapping scopes, they will find some speech-language pathologists practicing in the same space, especially when it comes to children with autism and other developmental disabilities in home, clinic, or school settings. Within this shared space, the potential for perceived and actual encroachment exists— and where skillful collaboration and professional humility are essential.

Understanding the Overlap

There are many areas of overlap between speech-language pathologists’ and behavior analysts’ scopes of practice. However, it is not as simple as comparing two scopes of practice (as the figure suggests). While American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) provides a single scope of practice that regulates the profession of speech-language pathology, professional behavior analysts may be subject to scopes of practice set forth by national organizations (e.g., Behavior Analysis Certification Board), state licensures, other disciplines (e.g., psychology, education), or other countries. Given there are several possible misunderstandings surrounding behavior analysts’ scope of practice when compared to speech-language pathologists’, behavior analysts should not assume their colleagues know which scope of practice regulates their work. Furthermore, it is the responsibility of individual behavior analysts to be transparent about their scope of competence. Regardless of overlapping scopes of practice and scopes of competence with speech-language pathologists, behavior analysts should be prepared to collaborate regularly and consult when necessary.

Within this shared space, the potential for perceived and actual encroachment exists––and where skillful collaboration and professional humility are essential.

Promotion of communication skills of children with disabilities is one area in which both behavior analysts and speech-language pathologists commonly practice. As they overlap in the teaching of communication skills, each profession contributes unique expertise and repertoires. Behavior analysts have strengths in measuring communication skills, especially related to functionally-defined verbal operants, whereas speech-language pathologists have a deep understanding of speech and language development. Operating from a behavioral perspective does not discount a developmental approach. For example, understanding the developmental sequence of sound acquisition is critical when developing behavioral programs to increase sound and word repertoires. Since this developmental understanding is not standardly included in behavior analysts’ training, consultation and collaboration with speech-language pathologists are critical. Other clinical conditions around which behavior analysts should seek the expertise of their speech-language pathology colleagues include, but are not limited to, fluency disorders, voice and resonance, swallowing, and feeding.

Behavior analysts teach communication based on their functions, defined by environment- behavior causal relations. While speech-language pathologists have indepth knowledge of language structures (e.g., syntax, morphology, phonology, etc.), they also assess and teach communicative functions, albeit following different definitions than behavior analysts. Speech-language pathologists categorize communicative functions by the communicator’s perceived intentions (e.g., behavior regulation, joint attention, social interaction). Different ways of talking about communicative functions is not a reason to avoid collaborating. Instead, recognition that behavior analysts and speech-language pathologists use different terms for similar concepts can serve as a foundation for increased understanding and respectful dialogue, which ideally build toward complementary and collaborative services. The ultimate goal of every treatment plan is to achieve the greatest outcomes for the client. Ensuring they benefit from all possible expertise and skills increases the likelihood of attaining that goal.

Behavior analysts should be actively engaged in learning at all times. Professionals from both disciplines can learn from each other and should do so for the benefit of their shared clients. Although not an exhaustive list, the table outlines a few relative strengths of each profession and areas around which there may be opportunities for collaboration and professional development. Importantly, these lists are not designed to describe every individual, but to reflect content that is routinely taught to students. Some behavior analysts will have strengths in areas on the list for speech-language pathologists while some speech-language pathologists will have strengths in areas on the list for behavior analysts.

Operating from a behavioral perspective does not discount a developmental approach and consultation with colleagues whose education and training includes a thorough understanding of child development should be standard practice.

Interprofessional Collaboration Competencies

In spirit of enhancing client outcomes and the capacity of professional behavior analysts to engage effectively within interdisciplinary teams, the ABAI practice board recommends that practitioners and the organizations that train them adopt the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice (IPEC) and actively seek to engage in interprofessional practice (IPP) and interprofessional education (IPE). The WHO outlines four interprofessional competencies that emerge from a set of principles and are not unlike those readily adopted by behavior analysis licensing bodies (e.g., client and family centered, community and process oriented, relationship-based, developmentally appropriate recommendations, sensitivity to practice differences, and outcome driven).

In INTERPROFESSIONAL PRACTICE (IPP), multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds work together with patients, families and caregivers and communities to deliver the highest quality of care. INTERPROFESSIONAL EDUCATION (IPE) is when students from two or more professions learn about, from and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes.

(WHO, 2010, p. 2)

COMPETENCY 1: VALUES AND ETHICS

– Work Together with Mutual Respect and Shared Values.Behavior analysts are charged with working respectfully with clients and families who differ by race, ethnicity, and culture. The obligation to embrace diversity extends to other professionals on a client’s assessment and/or treatment team. It is incumbent upon professional behavior analysts to engage with other professionals respectfully and with integrity, while validating alternate opinions and striving to build common ground and shared goals. This requires a great deal of cultural humility, which is the ability to be other-oriented when engaging interpersonally with people from different cultures. In general, behavior analysts and speech-language pathologists have strong cultural identities. The practice of cultural humility and cultural reciprocity (i.e., self-reflection and learning about individuals while avoiding assumptions) will strengthen interprofessional collaboration among professionals who come from different cultures.

COMPETENCY 2: ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

– Acknowledge Team Members’ Roles and Abilities. Behavior analysts clearly communicate to other professionals what their role and responsibilities are, what they can do for the client, and what expertise they can contribute to the team. At the same time, behavior analysts must be candid about the limitations of their skills and competence and strive to understand the roles and responsibilities of other team members. Behavior analysts should describe how their own practice can be augmented by the expertise of other professionals on the team (e.g., speech language pathologist), which necessitates self-reflection and cultural humility as well as understanding their colleague’s areas of competence. Behavior analysts should avoid making assumptions about another team member’s approach, role, and responsibilities, as there is great variability in the philosophies, opinions and expertise of speech-language pathologists.

COMPETENCY 3: INTERPROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION

– Communicate in a Manner That Supports a Team Approach.Behavior analysts use professional oral and written communication practices when engaging with an interdisciplinary team and individual colleagues. Communication should be positive, proactive, and oriented toward establishing agreements and resolving disagreements. Personally attacking others, criticizing another discipline’s research, or dismissing a colleague’s professional opinion reflect poorly on behavior analysts and the entire profession of behavior analysis. Active, empathic listening will encourage team members to share openly and reciprocate respect for behavior analysts’ contributions to the team. Genuine on-going conversations are needed to establish shared values and strengthen mutual respect.

COMPETENCY 4: TEAMS AND TEAMWORK

– Apply Team-building Values and Principles.The evidence-based practice of Applied Behavior Analysis demands the integration of the best available evidence with clinical expertise and client values and preferences. This framework, adopted by most human service disciplines, organizes team decision making and shared accountability. When evidence-based practice has been intentionally and explicitly established as the team’s process, the team does not need to rely on any one member’s clinical opinion. Instead, rigorous scientific research and client and family preferences are given proper attention and consideration alongside clinicians’ expertise and judgment. To the extent that evidence-based practice is a team-based, decision-making process, the team (not an individual) is responsible for client outcomes and share the responsibility of problem solving for the good of the client. However, individual team members, including behavior analysts, are responsible for contributing to the improvement of the team’s process and overall performance. Behavior analysts have an ethical responsibility to help carry out the team’s plan even when the team’s decision does not align with their own. They are urged to go beyond just cooperating with speech-language pathologists and other colleagues, which implies each professional works on individual goals. Real collaboration involves working together to accomplish joint goals and integrated care.

Benefits of Interprofessional Collaborative Practice

There are clear benefits of interprofessional collaborative practice to clients. It prevents unnecessary replication or conflicting treatments, reduces the cost of care, and promotes high quality comprehensive service delivery. For practitioners, interprofessional practice creates enriching professional and personal relationships and fosters professional growth and development. Interprofessional collaboration fosters a culture of teamwork among the contributing professionals which heightens treatment adherence and fidelity, increases generalization opportunities, and sustains effective team performance. Finally, when behavior analysts engage in interprofessional collaboration, the field of behavior analysis and a world of potential clients benefit. Genuine demonstrations of cultural humility increase the influence of the science of behavior because non-behavior analysts may be more willing to learn about it. The public image of behavior analysis can be one of interprofessional respect and collaborative effectiveness, which will ultimately prime the practice of behavior analysis to benefit society in meaningful and scalable ways. In essence, behavior analysts can more productively act to save the world.

The public image of behavior analysis can be one of interprofessional respect and collaborative effectiveness, which will ultimately prime the practice of behavior analysis to benefit society in meaningful and scalable ways.

REFERENCES AND RESOURCES FOR FURTHER STUDY

Brodhead, M. T., Quigley, S. P., & Wilczynski, S. M. (2018). A call for discussion about scope of competence in behavior analysis. Behavior analysis in practice, 11(4), 424-435.

Carr, J. E., & Nosik, M. R. (2017). Professional credentialing of practicing behavior analysts. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 4(1), 3-8.

Collaborative Practice: Report of an Expert Panel. Washington, DC. https://ipecollaborative.org/uploads/ IPEC-Core-Competencies.pdf

Esch, B. E., & Forbes, H. J. (2017). An annotated bibliography of articles in the Journal of Speech and Language Pathology-Applied Behavior Analysis. Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 33, 139–157.

Interprofessional Education Collaborative. (2016). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 update. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

LaFrance, D. L., Weiss, M. J., Kazemi, E., Gerenser, J., & Dobres, J. (2019). Multidisciplinary teaming: Enhancing collaboration through increased understanding. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(3), 709-726.

Slocum, T. A., Detrich, R., Wilczynski, S. M., Spencer, T. D., Lewis, T., & Wolfe, K. (2014). The evidence- based practice of applied behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst, 37(1), 41-56.

World Health Organization. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en

Wright, P. I. (2019). Cultural Humility in the Practice of Applied Behavior Analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(4), 805-809.